Murals by Michel Castaignet and August Künnapu in Kuldīga Artists’ Residence, Latvia. We got to know each other 6 years ago in Kuldiga Artists' Residence in Latvia, where we both made murals. Also Inga Meldere from Latvia and Anne Rigoulet from Japan participated in this art project. I remember that after 10 days of hard work we both had a natural massage in the local river under the waterfall. What are your memories of that time?

I also remember this waterfall with delight. It was funny because when we were driving there from Riga, we’ve been told it was one of the biggest in Europe. So, I imagined some sort of Niagara Falls, to discover when we arrived that the fall was only about a meter high and it was in fact one of the largest or longest fall in Europe, not the highest. But indeed, it was lovely hanging out there. I also remember there was a sauna in the house, which for you is nothing unusual but for me it was the first time I went to a private Sauna. And Uldis set the temperature super high, I was literally cooking. Talking of cooking, Anne also made a Japanese meal for us, that was very nice. I also remember the city was very cute, with its wooden houses. I went back there a few years later when the French Institute organised a Design exhibition there, but unfortunately, I couldn’t get inside the house where we did our murals.

You made another mural year ago on the facade of a building in Jussey, a French village in Franche-Comtes. That was probably a totally different experience.

Yes it was. I was the only artist in the residency, and I was housed at farmer’s, so the evening meals were less arty than in Kuldiga. We talked a lot about the animals, the crops or local politics. They also fed me so much that I took on 10 kilos in a month. Then the mural itself was very large, 11 by 7m, so I had to use a scaffolding and I had a bit of vertigo when I was up there, I regretted not having taken assistants. It was also an outdoor wall, facing south and there was a terrible heat wave at the time. There was a little fountain in the street and I kept climbing down the scaffolding, drink at the fountain, climb back up, at the end of the day I was exhausted. I also had planned to go the Basel since the village wasn’t so far from it, but my car broke down, so I stayed in the village non-stop. There were also some funny moments, I did some interventions in the local schools, so every morning the kids would call me on their way to school and come to see the mural progress. There was also a nasty old woman who came most of days to tell me she hated what I was doing. Then when I finally finished, it took me a week longer than expected, there was a very official ceremony with local politics because this mural was commissioned for an anniversary. So in a way it was not as nice as Kuldiga, but I made more money.

Mural by Michel Castaignet in Jusey, France, 2019. Did I remember correct - at the end of eighties you used to live as a teenager in London, where you made visuals for the freshly born rave-parties? What did you learn from that experience?

Not really in fact, at the end of the eighties I was in Paris, I came in London in 92. So, I experienced Rave parties in France but when I moved to London, the movement had died out and the techno scene was in the clubs. I made some visuals for two clubs during special experimental parties. They were movies made of found footages, but that was very house made, nothing to do with the elaborated VidJeeing that we have nowadays. I don’t know what I have learned from that honestly, I took it as an amusement because I liked dancing and was eager to participate a bit to the mood of the room. Maybe what I’ve learned from this time is that cities change rapidly. When I came to London, the city attracted musicians and artists, eight years after the city attracted bankers and people who wanted to make money. The city was then very different from one borough to another, every place had its own vibes. Now the city is like a mega shopping mall with every single high street looking the same with the same shops and restaurants. It’s ruined, and it happened so fast.

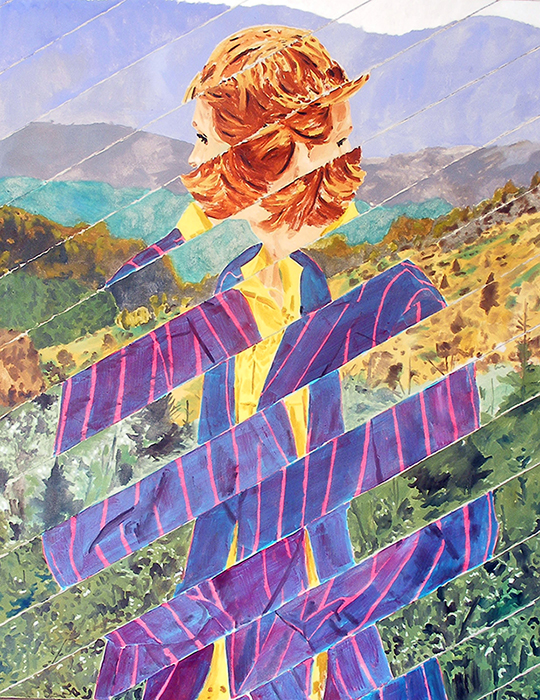

Michel Castaignet. Wandern.

Oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm, 2020. You have studied aesthetics and art theory in Middlesex University in London. How did you start to paint?

I started painting much before I studied aesthetics, I started painting, or more specifically drawing when I was a kid and I studied Aesthetics when I was 28. In fact, I engaged in philosophy in order to respond to question I had about painting and art in general. When I was 18, I didn’t really know what to do so I register in mathematics at the university, but on the side, I was publishing comic’s in a Parisian gay newspaper called Exit for one or two years. I came from a totally non creative family, so I didn’t know being a painter was an option. Mathematics was good because it sounded serious so my parents would pay for my flat in Paris, but I was more interested in the Rave party scene than in Euler. Then I stopped after three years studying, which is not a good move because in Science if you don’t have a PhD you’ll end up in not so interesting laboratory job, I discover that working in a pharmaceutical company for two months after my studies, so I move to London out of curiosity and in order to escape family pressure to take on a job and start a career in something I wasn’t really found of. Once in the city, I felt freedom of movement, I wanted to do comics but my poor command of English and the lack of a comic’s scene as we have in France and Belgium, disappointed me, so I started painting more seriously. I then met other artists who told me I couldn’t be self-taught if I wanted to make a career, so I toyed with the idea of doing an art school but never register. I had this idea that I didn’t need practice because I was already painting, which of course is a wrong idea because in school you can also get a direction in your work and I would have needed that, but at the time I didn’t know it. So, I saw this master in Aesthetics, they took me on, and it took me two years to do it because philosophy was totally new to me and I had to do a lot of reading. When I graduated, I decided to go back to France as it would be easier for me since life was cheaper then. I took on a studio and start painting non-stop until today.

Michel Castaignet. Traversee.

Oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm, 2011. You have an interesting balance between figurative and abstract in your work. Both colour and form seem to be your good friends.

Yes, I always feel in a swing. When I do some figurative work for a few weeks, I then feel like doing abstract, and the reverse apply. Now I try to combine both in the same painting although its antithetic, a painting is figurative or it is not. I think it come from that I have very various interests in paintings, I like as much Sean Scully, Francis Bacon or Balthus. Some people will only like one genre of painting and it’s easier for them to pursue in one direction. As for me I live in a mix of images, a bit like electronic music where you can add any beat you want. About form, yes it interests me a lot, I’m making carnets with shapes drawn on them when I’m at home, like if I was making a collection. Sometime I draw on them to start a painting but most of time they just stay in the carnets, I might do something of them later. Colours, a great interest as well, maybe sometimes too much of them, but I never managed to limit myself to a simple two or three colours, I always end up with many flashy colours all over the canvas. Apparently, I’m slightly colour blind say the tests, although it doesn’t impede me in my daily activities, I don’t mix up red and green, maybe I don’t see the colours like other people do, so maybe that’s why I like using them.

You consider yourself a nomadic European artist. Please compare your three living and working places in Berlin (Germany), Champagne (France) and Syracuse (Italy).

Champagne is my oldest atelier and the biggest, so I have all my storage there. I produced good work there but now when I come back, I spend more time checking old paintings than producing new ones. Plus, when I’m in France I have to deal with all the administrative things since I’m still register as an artist in France and I don’t come so often, so when I’m there, there’s a lot to do. So lately I have not produced much in this atelier, so I could say it’s my dead atelier, but it might not stay like that, it’s very big and has a lot of potential.

Berlin is my main atelier, I’m working very well there, although it is not very big (40 m2). I’m in a block with 300 artists, so I thought at the beginning that it would be very busy with a lot of emulation, but finally I never meet anybody because I arrive early on the morning and leave at dinner time without any break and I think the other artists tend to come more in the evening. Although I really like this atelier I might have to change, it is a bit too far from my house. In Berlin distances are enormous, I’m more than one hour away from my atelier and the atelier is also around one hour away from the galleries. In Paris I used to go early in the atelier, work there and then visit some galleries before I come back home. In Berlin if I wanted to do the same thing, I would have 4h transport a day so it’s not sustainable. So unfortunately, I’m not visiting galleries as often as I would like and after 3 years in Berlin, I only know a handful of them. So, my plan is to work nearer from home so I have time to visit galleries. Maybe wishful thinking because there is l less and less ateliers available in Berlin.

As for the atelier in Sicily, it’s a long-term project, so far, I’ve been painting outside because it’s not finished. I bought a big land in the mountain and we’re slowly building the house. I’ve been working several times there and it really has transformed my work, it has pushed me toward more abstraction. Usually in the atelier I have photos, documentations, old paintings, a lot of things that channels my ideas. In Sicily I have nothing, just a box with my colours, some canvas and great landscapes. At first, I thought I would paint landscapes, but that didn’t really happen and I went toward a very abstract language. Actually, I’m really looking forward to go back there for a long period and paint, I just have to wait that the coronavirus situation settles down.

Michel Castaignet. Trace.

Oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm, 2011. Among many other places you have made 4 painting exhibitions in Maksla XO Gallery in Riga. I have seen 2 of them - they were wholesome, lively, idiosyncratic, with a sense of style and good exhibition design. How do you like Latvian contemporary painting and how does your work fit in this culture?

When I first came to Latvia I discovered a hanging tradition that directly came from the Soviet Union, I was puzzled to see that people would show in galleries that were not white cubes and using picture rails so it was quite interesting, because in France we were told better not show than showing in a bad condition. I remember after my first show, I photoshoped out the threads from the picture rails so I could show the photos in France. But now I don’t see much picture rails in galleries in Riga.

But now I don’t see much picture rails in galleries in Riga.

About Latvian paintings, I don’t know, I’m not really an expert, I come once a year or every two years to do my show and I don’t stay very long. More or less I only know the artists that Maksla Xo exhibits because I see them also during the Vilnius, Berlin and Vienna Art Fairs and I can read their catalogues when I’m in Riga. In fact, I don’t see any regional particularism, paintings tend to be very similar worldwide. Maksla Xo has nevertheless some artists with a strong visual identity, such as Heinrihsorne,Gelsis, Ilterne, Liepa, but I don’t know if I would see something typically Latvian in their work. And consequently, I don’t think my work has something particular to offer to Latvians, as opposed to other countries, they are just paintings that you might like or not. Maybe yes, there is something of my work that fits well with Latvia, they like colours. I’ve never been told I was too colourful, unlike in France where the more brown/grey your paintings are, the more the public likes them.

Michel Castaignet. Le retour.

Acrylic on canvas, 130 x 160cm, 2016. You gave me as a present your book of paintings in Kuldiga. I noticed that the texts in this book are in French, English and Russian. What do you find interesting in the Russian culture?

Well, the book included Russian text because in 2010 I participated to the French Russian cultural year and I did several shows in the following years in St Petersburg, Moscow, Vologda and even one in Kazakhstan, so it was handy. Plus, when I exhibit in Riga or Vilnius, the people who don’t speak English usually speak Russian. So, in a way it was strategical. But I do have an interest in Russian culture as well. When I was a teenager, I studied Russian for two years at school as a third language, I couldn’t do more because I went then in Science course where only two languages were mandatory (I did English and Spanish). But I always kept my Russian books at home and often tried to learn further. As a kid I was mesmerised that they use a different alphabet and for secrecy I was writing my diary in French using the Russian alphabet, so nobody would understand. I also had a period at university when I was devouring Russian classics like Dostoyevsky, Pushkin, Gogol. I later discovered the landscape school of the 19th century and really fell in love with Levitan. I was touring Russian a few years ago and in Saint Petersburg, which was my first stop, I bought a monography of Levitan, the book was around 5 kilos and for one month I had it in my backpack and I was hating myself for having bought it on the first day.

About contemporary art in Russia, I’m very admirative of their performance scene, from Kulik to Voïna, they really take risks. In France the performance scene so called political is a total fraud, they work hand in hand with institutions in order to criticise the institutions while being paid by the institutions for being so rebellious. I mean, how boring. In Russian they really dare to oppose the system and that’s really interesting that they risk their life for the sake of art. That’s something I’m a bit jealous of, as a painter in these times the occasion to show courage are scarce.

What has been the most difficult and the easiest moment in your life??

I think the easiest was when I was a student, life was cheap then, I had a small job a few days a week and I felt rich, I was going out a lot and studying was easy for me so I never had any problem. The most difficult part is coming now, my parents are aging and start having problems, my gran has Alzheimer, a good friend of mine is in a coma. With age start problems. It’s difficult now to go to the atelier and pretend everything around disappears and only creation matters. During the whole summer I hardly painted, I was calling the hospital every day to get news of my friend, and then what they told me stayed in my mind and I was not in a mood for painting. Unfortunately, I’m afraid life will be more and more like that, parents dying, friends dying and as an artist I must find some selfish space in my mind to keep going.

You are currently writing a book about French painting. Which periods and authors are you paying attention to? What kind of new discoveries have you made while working on this project?

That’s a very early project, maybe it will be a book maybe an article, depends on the size. I’m interested in the situation in France at the end of the 90’s and all the years 2000 where there were no more French painters in the galleries and art school were discouraging young artists to take on painting. Last year the Villa Medicis (The French Institute in Roma) did a survey on the vitality of French paintings, the study was conducted by painter Thomas Levy-Lasne and Curator Isabelle de Maisonrouge. There conclusion was that French painters were plenty and now well represented by galleries, so we could not say anymore that painting was dead in France. They isolated 120 painters and when I looked at the list, I noticed that at least 90 of them were from my generation, so raised at a time when painting was persona non grata in France. Their work is very diverse so it is not really possible to talk about a French school of painting, like you have the Leipzig School in Germany. But my thesis is that despite the diversity of the forms, all these works are linked by the conditions of their apparition on the art scene, i.e. the situation in the 90’s and 2000’s.

Michel Castaignet in his studio in Berlin.

Photo: Axel Palhavi. Nowadays it is popular to bring to art all kinds of social themes and the format of research. Are they really necessary in art?

They shouldn’t be. I mean some art is definitely political but not all of it so it shouldn’t pervade on all forms of art. For me the real political value of art is its ability to exist, so all the rest is just dress up. Now a show is set up by a curator paid by an institution, so basically many people are involved who are not artists, so they want to work on something concrete and fashionable. Therefore the text, the dressing up, is very important. If you work for a foundation set up by a bank or a big car manufacturer, it’s always better to say that you’re showing an artist who’s trans black feminist and tackles the environmental issue than saying you exhibit some guy who paints cats. Just by naming the subject that you finance makes you important, fashionable and make people forget the money might come from child labour in India. Art in the age of advanced capitalism is often just cosmetics.

What makes painting a PAINTING?

Paint interestingly disposed on canvas. If you look at a guy like Merlin James, he did a lot of experiments, sometimes with transparent canvas, and all of it works well despite poor technique and no will to impress. Going back to this list of French painters established by the Villa Medicis, in fact, the researchers contacted us and asked us to name two other painters alive that we thought were important. When you look at the results nobody named Rutault, Buren, Viallat, all these historical figures who wanted to push painting out of the canvas, all the historical schools like Support/surface and BMTP were not considered by the present days painters as real painters but rather as contemporary artists. But if Merlin James was French (and alive), I’m sure he would be on the list. So, I think you can experiment as much as you want, there’s no rule in painting, but if you leave the canvas, you leave painting. Now the question could also be what makes a good painting? And that would be trickier to answer because it so depends on taste. And taste also evolve during lifetime. There were painters I hated younger which I find interesting now, and the reverse. So, I wouldn’t know how to answer to this one, I’m glad that was not the question.

More info about Michel Castaignet: castaignet.com

AUGUST KÜNNAPU

Editor of Epifanio and a painter |